Ben Lerner on The Hatred of Poetry

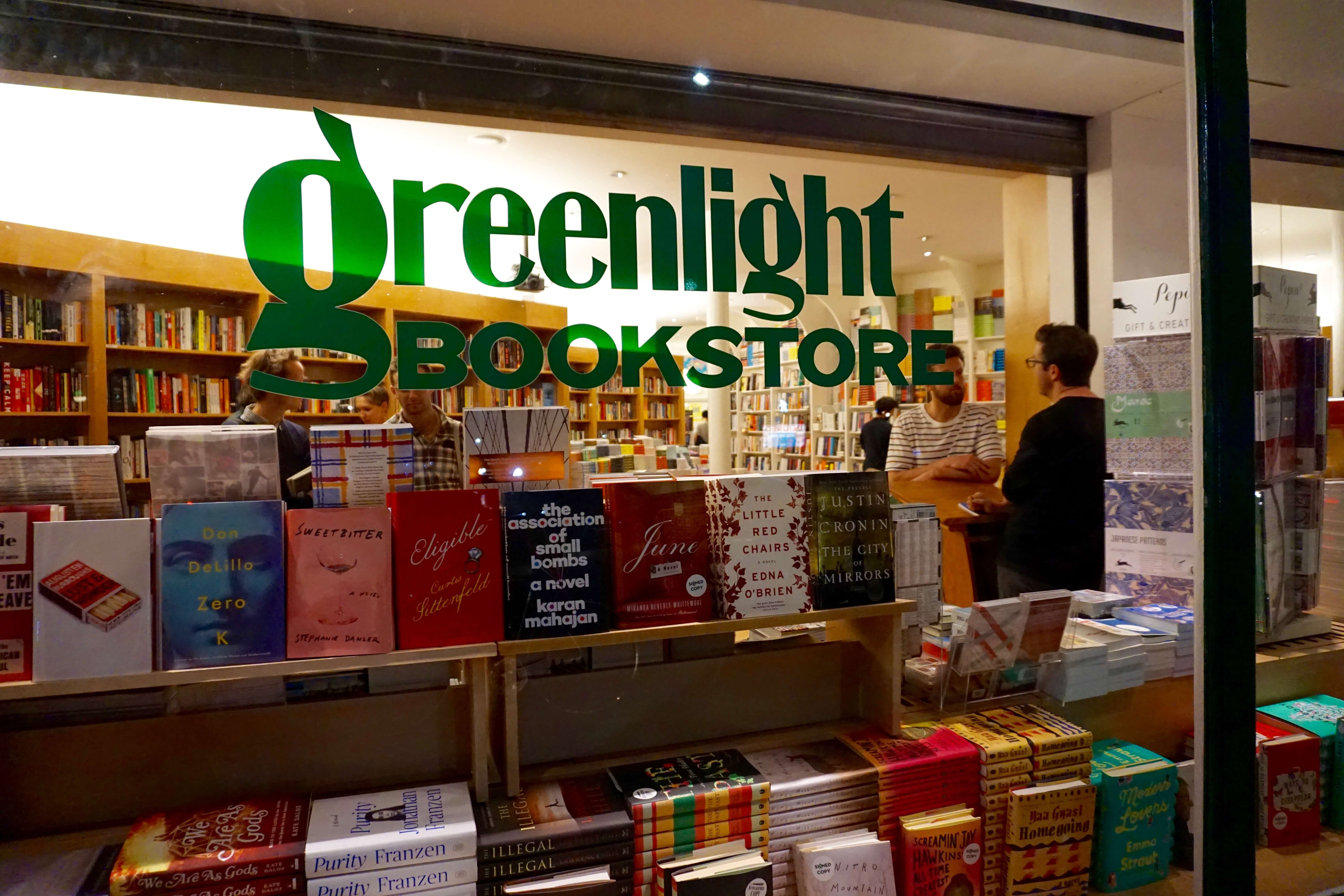

June 9th at Greenlight Bookstore, Brooklyn

The Hatred of Poetry, the latest release by poet-novelist Ben Lerner, is a declaration of tough love. Leaning hard on Platonic ideals and Negative Theology, Lerner draws up allegorical parallels to trace an outline of Poetry’s definition by marking off everything that it is not (yet strives to be): Universal, Virtual, Absolute. By nature, the Poem—like the Ideal, the Virtual or the Apophatic god—is not, because it transcends actual being; and thus, the poet—with her adorations and anthologies—does labor.

“I, too, dislike it.”

Lerner’s personal hatred of poetry is traced through historical example: the bombastic avant-garde poets, nostalgic, futuristic and individualistic poets, the wide-eyed universalist poets, and the just plain terrible. But he locates the root of his hatred early on: as a high school freshman, young Lerner is asked to memorize and recite a poem, so he maneuvers for the shortest at hand—Marianne Moore’s “Poetry.” Though aptly named for these purposes, the poem is a decidedly clumsy work and Lerner is unable to recite it, spare the first line: I, too, dislike it—a phrase, he claims, that “has been on repeat in [his] head since 1993….a kind of manic, mantric affirmation.”

I, too, dislike it is chanted throughout the book, directly and not, to empty out the history of poetry as a history of nothing doings, of negative space. Poets, it seems, hear the angel in the marble but fail to release her—this is the virtual ideal that poetry strives toward. Lerner—like many a poet, neighbor and small talk dentist—is kicking at the marble dust on the floor pronouncing what is perhaps the only universal claim to poetry—a hatred of it: I, too, dislike it.

“When we experience a poem’s radical failure, we must be measuring it against some ideal, some Poem.”

Mapping out the virtual and the actual as poles between which the Ideal may be glimpsed—or more aptly dreamt—Lerner sets up poetry as a process art, and hatred of it as the poet’s necessary labor. The virtual poem is contaminated by the technology of writing it—the actual. Poetry, to Lerner as it was to Dickinson, remains the intangible no-place, the fairer house of “Possibility” that is only an “immaterial dwelling, all threshold and sky.”

This template of the virtual/actual is a handy gage, yet what is most edifying arrives in Lerner’s investigation of that transient delineation between—the virgule (“ / ”): “The virgule is the irreducible mark of poetic virtuality—the line break abstracted from the time and space of an actual poem.”

Etymologically, the virgule proves a vivid prism: “Virgule” from the Latin virgula, meaning a little rod, as in Virgula Divina—the divining rod that “mediates or pretends to mediate between the terrestrial and the divine;” the parallel is well exemplified by Dante’s own mediating guide, Virgil.

Virga—the phenomenon of falling rain or snow that evaporates before reaching the ground—just happens to be Lerner’s favorite type of weather: “it’s a mark for verse that is not yet, or no longer, or not merely actual…phenomena whose failure to become or remain fully real allows them to figure something beyond the phenomenal.” Great poets, Lerner finds, either fall silent altogether or confront the Poem in the fashion of his virga. These individuals create poetry of impermanence or, as a filmmaker once found it, insecurity; the rarefied atmosphere about such art renders it “fragile, fleeting, revocable.” It is the phenomenal with intention, suspended and ever vulnerable—as tilted rain that does not fall, but floats—to transcendence.

“You can only compose poems that, when read with perfect contempt, clear a space for the genuine Poem that never appears.”

During last Thursday night’s reading at Greenlight bookstore—a considerably packed, hot and pleasant affair—Lerner covered much of The Hatred of Poetry with writer/critic Michael Clune, in addition to relevant discussions of Occupy Wall Street, Grossman, Whitman and Adorno. He read a selection from Hatred in a lyric style, characteristically dangling form between poetry and prose. From my blind spot behind an inordinately tall boy of polyester, my senses were especially tuned into his wording, and I noted how even Lerner’s speech was hanging about the virgule:

While discussing Barnett Newman, Lerner mistakenly replaced the word “canvas” with his home state of “Kansas.” I was immediately brought back to the The Hatred of Poetry, its margins spotted here and there with something like footnotes, or rather sidenotes—thoughts left to float in the empty space, outside of the formal page. One such coupling on page 79 is “Vanish or Varnish” and, like “Canvas / Kansas,” marks Lerner’s definition of poetry, and surely art, as decidedly personal:

“If you are five and you point to a sycamore or an idle backhoe…and utter “vanish” or utter “varnish” you will never be only incorrect; if your parent or guardian is curious, she can find a meaning that makes you almost eerily prescient…the backhoe has helped a structure disappear or is glazed with rainwater…To derive your understanding of a word by watching others adjust to your use of it…I think that’s poetry.”

The Hatred of Poetry truly is a loving apology, in all the nuanced definitions of the word. It defends the good along with the bad, while commiserating regretfully with poets and “non-poets” alike. I loved this little green book for all its didactic anecdote and negative space, Platonic refreshment, and stirring mediations on Dickinson, Whitman and Rankine.

However, I perhaps most enjoyed hearing Lerner unknowingly demonstrate his own method last Thursday—and succinctly summarize this complicated relationship of his—while relating his experience of watching Philadelphia on a recent flight. Admiring Tom Hanks’ monologue on opera, Lerner admitted, with a small sigh: “I get emotional in the air.”

*Chris Marker / Text from Sans Soleil

April Gornik, Virga / 1992, oil on linen, 90 x 76 in. Smithsonian American Art Museum

Sidenote:

North / Carolina

“I loafe and invite my soil, / I lean and loafe at my ease observing a spear of summer grass.”

As in The Hatred of Poetry, Clune and Lerner discussed Whitman at length as the well-meaning Universalist (“to be no one in particular so he could stand for everyone”), caught between the Civil War, the North and South: “I am the poet of the slaves, and of the masters of the slaves.”

Truly, Whitman—the poet-loafer that transcended life, labor and “America”—was much closer to virga than a solid democratic ideal. Walt that mediated between the North/South, the Yank/Rebel, the Master/Slave, the poet that tends to everyone as “they are sacrificed for the future union;” and yet, Lerner lovingly notes, “he cannot fight.”

Whitman’s efforts, though full of I’s and contradiction, do swell with a sweet air—emptied and ready. Following the reading at Greenlight, I quickly recollected one my first interactions with the Kosmos below, as a young girl loafing about my own version of Canvas/Kansas:

I picked up Walt Whitman’s Specimen Days when I was quite young, having previously digested a few leaves of grass. I read it from my trundle bed, musing as to how not only was he a nurse like my mother, but how he—a Yankee poet—could be caring for Confederate soldiers.

As I said, I was quite young and the confederate flags still licked a few of the poles around our small North Carolina town. Men still idealized Davis and Lee, and guarded closely their X blind pride while naming their guns, dogs and daughters after the Butlers, O’Haras and Bible characters. The South has never recovered from its failure—not to win, but to awaken—and sucks hard at the root of Antebellum. Most dig as fervently for their Confederate ancestry as the mountaineers do their ginseng, and I myself have inherited one yellowed picture of a poorly decorated however many greats Uncle that stares out from the drawer, next to his rifle and confiscated Union cap; a man that I at first mistook for our Walter—hat and eyes atilt ( / ).