Sweet red wine in the morning on hard concrete steps with a shot girl and her sick soul and her hands clenching; and a French guy on long vacation so handsome he’d turn his girlfriend’s mother into a betrayer; and a middle-aged guy who sculpts animals out of gnarled driftwood he hauls from the Mississippi River and who looks himself as if he is sculpted from driftwood and hauled from the Mississippi River; and a young woman from Vermont who is wearing purple tights and carrying a fresh-picked orange in the pocket of her sweatshirt. She offers me the orange, I politely decline, and she returns it to her pocket. A few minutes later she retrieves the orange, cocks her hip, and says, “Come on. You want this orange.” “I’ll take the orange,” I admit. I catch her toss and hold the orange. “Share it,” she says. The new room Isabella and I share at the weekly rental place is empty except for the bed. The walls and ceiling are white. When the sun rises the room remains dark except for a white patch where the one small window is, vine leaves crawling like spiders across its surface.

The song “I still haven’t found what I’m looking for” comes on the radio and the driftwood guy remembers: “This is last song I heard before they come and got me. It was playing on the radio when they come.”

Purple tights says, “Who came and got you – Bono?”

“No. They come and got me. Took two years of my life.”

I ask, “Were you able to listen to music while you were inside?”

“Nada. No sir.”

To the French guy, who’s having difficulty following us, I say, “Je suis un grande pamplemouse.”

“Qu’elle q’uon fois?” he replies, charmingly taken aback.

We pass around the wine. The girl with the fluish spirit tells a story about dumpster diving at a gas station, eating the food she’d found, realizing the clerk at the gas station had poured gasoline on it. Purple tights wide-eyed remembers a story she’d heard about a kitten in Vermont who wandered into a meth house and the people there had doused the kitten with gasoline. I imagine the poor thing tweaking off the fumes and trying to shake the gas from its little body and I laugh really hard, saying, “Oh my god.” Purple tights watches me with curious delight. I squeeze the orange and feel shy.

My first vision of my friend Pongo: bellowing out his poetry at a place downtown that served “legal highs” – kava kava and teas made with kratom, a man in carpenter jeans and wife-beater, strong arms trembling as they flung page after page to the carpet – lines about digging graves with shovels made of blood for a handful of kava-dazy teenagers leaning against their backpacks. He wore a fitted Atlanta Braves cap, which he always wore, I would learn – he had several fitted caps, but they were all Atlanta Braves, exact same design. “Gotta keep the ace on top,” he told me later. A huge muddy red beard, freckles on his thick shoulders. This guy is a maniac, I thought. I caught eyes with my companion, an astrophysicist who was visiting me. She barely nodded; she was thinking the same thing.

The astrophysicist: lithe, shattered smile, espresso curls, whispers of silver, expensive jeans, lacy mouth. She had tried to shoot herself through the temples once but her hand jerked and the bullet soared in front of her eyes and now gunpowder was permanently pleated into her wrist and, it seemed to me, fire-dust and horror still glittered in her eyes.

After the reading, on the sidewalk, I sipped chilly kava kava from a wooden shell, a sliver of pineapple floating in the earthy puddle. Pongo stood alone so I approached and offered him an American Spirit which he declined – he was asthmatic. But he joined us awhile later at the Yacht Club for Sailor Jerry and pineapples with splashes of ginger and Pongo grinned the whole time like a guy who’d just gotten out of jail and was on his way home to see his sister. We listened with chilly enthrallment while the astrophysicist spoke about the theory of heat death.

The astrophysicist and I went on to share a romance brief and sad and gorgeous as redness draining from a blood moon or grenadine sinking down a small glass of tequila; and Pongo and I would become great friends until the icy March morning when he placed a six-hundred dollar black-market Glock to his heart and splashed himself across the back of his silly green polyester armchair.

Jerry in the doorway was shirtless with fat-rolls burbling like toad throats over his waist and his bald head sweating, the color of canned salmon. He returned to the bed in the center of the motel room, lowered himself onto it, found his flyswatter and scratched his back. All his possessions were falling out of distressed lawn and leaf bags and the fluorescent overhead was flickering and dull and his pit bull Daisy wheezed in the corner, saliva streaming from her black gums. Jerry smoked and scratched and told me about the drive from Philadelphia. The heroin was apparent in his eyes. The astrophysicist knelt and patted Daisy. Pongo stood by the door, smiling all around. I bought fourteen grams of heroin and a prescription bottle filled with Oxycontin, thirty milligrams apiece, at a very good price, and I hurried up and got us out of there. The stars were visible in the crisp, clear night and the astrophysicist took my hand. She laughed and exclaimed – “My god, what was that?… I feel like you just led us to Hell!”

Isabella suggests I take a walk so I walk around the new neighborhood in Treme, turning at random corners, hands stuffed in the pockets of my hoodie, my right hand curled around the fresh orange, hair falling over my eyelids, looking sideways. Faded limes and peaches of the paint on the house-fronts, Mardi Gras beads dripping from the bare branches and the wrought iron and the mailboxes, black girls in their school uniforms – khakis and bright yellow collared shirts – skipping along the cracked and jagged sidewalks, the community center, the Catholic church, the liquor, beer, and cigarette shop, the abandoned buildings, plyboard over shattered windows, messages scrawled in paint over the plyboard – R.I.P. Wimpy J; End Poverty; home is a fleeting feeling – the setting sun like rouge smeared over a tired face. Isabella was right: I do feel a bit better. It had been a night of suffering. A dream in which an evil version of my father swiped at my eyeballs with a boxcutter and gouged his fingers into the terrifying wounds; a dream in which Isabella, over a misunderstanding, drenched me with a glass of wine then pulled down her pants and peed on my legs and feet.

There is a small tower of cinder blocks outside a building whose eyes are blacked out with garbage bags. It’s a nice perch. I sit, crack my neck, peel the orange.

My brother Alex and I didn’t have any money – but he had a quarter ounce of dried psilocybin mushrooms and I had a quarter tank of gas in my car and seven dollars on my EBT card. We went to Ingles grocery store and bought two blood oranges and a pack of frozen edamame, and drove slowly the backroads to the Blue Ridge Parkway, the bag of edamame on the dashboard, warming in the late summer sun. North, winding through the trees, to Graveyard Fields. We sat in the grass and ate the drugs, stems and caps pinched to snaps of the thawed soybeans, dirt and chewy membranes and salty bursts of juices. We started up the trail. The come-up was nauseous. Alex had to veer off and puke on some rocks. But I held my bile down and after awhile we were both yawning and cartoony and ascending the mountain as if on an escalator. Alex and I had tripped together on occasions before this one. They had been long trips, happy and frustrating. He is a quiet person, folded into himself like a paper plane; like a paper plane, when he’s tossed on drugs, he opens and soars… but then he lands on his side, and folds in again, and over-talk can be abrasive for him. I tend to talk too much in these times. Our journeys have gotten strange and semi-hostile. This time, though I was peaking neon and wanted to tell jokes, I remembered to stay quiet and let Alex commune with the nature along the trail; in this mood, I found myself plugged in in a major way to what was going on around me – wet knots of leaves, squirming soil, spiraling grooves pitted into two-stepping pines, schmoozing water and stones in pale slow streams; everywhere around me I saw roiling vaginas. Roiling vaginas, roiling vaginas. We continued on in silence. At the crest of the trail there is a crawl-tunnel of petrified wood which leads to a clearing carpeted with the softest pale spongey moss. There are blueberry brambles; the berries are ripe and blink like rubies. The sky softens and there is a sepia feeling to it; the sun is flames and clay and a woman peacefully glistening like the Origin of nature and unspooling her hips and her vulva and she is wet, life wet, and ever-opening and with two thumbs I peel apart the blood orange and she is dripping sweetly onto my face as I hold her above me and slowly bring her to my mouth.

Isabella and I are at a place called Kajun’s, empty, cigarette machine, stately old gay bartender. There’s a bottomless mimosa deal and we’re determined to drink until they’re out of champagne. Mimosas, poinsettias, whatever it’s called with cranberry. We have all the colors in front of us. There’s nothing on the jukebox and Judge Judy on mute on the TV.

“We got away with it,” Isabella says.

(We got away with what, them dying instead of us?) “We got away with what?”

She points at the TV, Judge Judy, she points at her champagne glass, smudged with her lipstick, she points at her tits one by one, at my cock, at my face.

“This is a hell of a deal,” Bella says.

____________________________

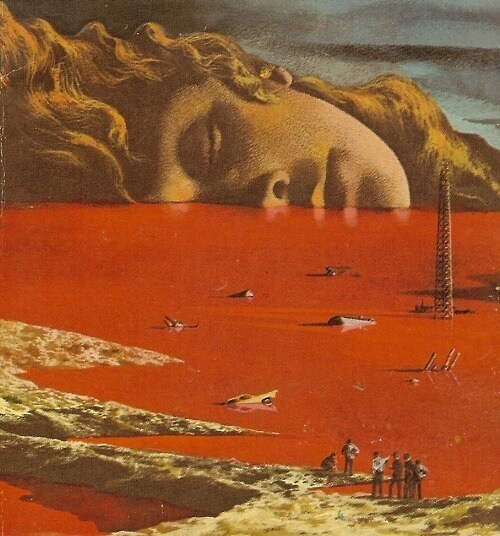

art by Karel Thole