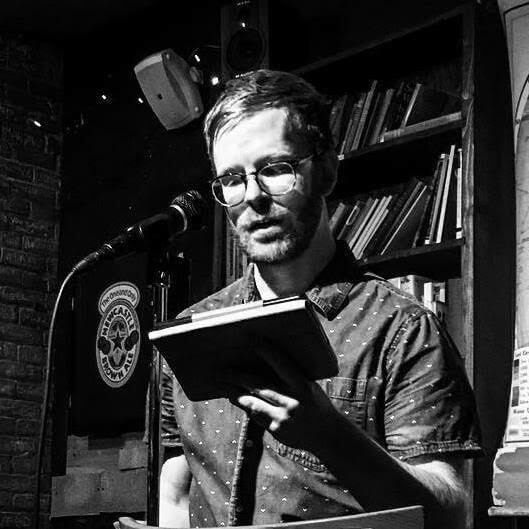

Stephen Langlois reads his story Talking Car

It started with a cough. I’d turn the key and the car would cough. Like a throat-clearing almost. Like raspy enough where maybe at first you could just pass it off as a worn out engine.

This car, after all, was thirteen years old, had something like two-hundred thousand miles on it. It was a yellow hatchback, rusted in spots, all scratched up in others. Nine hundred bucks cash: That’s what I paid for it. The ex-wife–well, she had the house, the kid, the Volvo we’d bought together three years back. Me, I had this coughing car now.

Time passed, the cough became a kinda deep, hateful hacking.

More time passed and–no other way to put it I suppose–the car started talking.

“No more,” it muttered one day. Confused, I fiddled with radio knobs, but the radio just sizzled static. I scanned the sidewalk for passersby. No passersby were to be seen.

Wondered maybe if I was imagining things. Thinking of all the time spent alone in my apartment this didn’t seem so unlikely. I drove away.

“Steel is steel,” the car groaned at me. “Death is death.”

Startled, I swerved into the oncoming lane, swerved back just in time.

“What?” I blurted, blushing at the ludicrousy–the insufficiency really–of such a question.

“Not now,” this car told me. “It hurts too much.”

A miracle of vehicular speech is what it was. How else really to describe it? An unknowable cognizance emanating from motor, released via vibration of metallic frame.

“The alloy,” this car was moaning. “The alloy hurts too much.”

Okay–so this car was something of a downer when compared to the kinda talking car one might see on TV. Really, this car was on the depressive side. This car had a bit of an existential streak if we’re being honest, but that I suppose is what I related to.

I began to welcome its voice.

“Feel my steel, I‘ll feel your death,” it would tell me, laughing bitterly: A harsh, joyless clicking. A cold, mechanized humor not contrived for man’s understanding.

But things being the way they were–well, it was something to hear besides the thoughts in my own head. Days off, I drove around solely for the company. At red lights, I sensed the stares of other drivers as I conversed with no discernible being.

“What happens when you’re parked?”

“Dreams,” the car told me. “Terrible dreams. Oil dripping. Sun burning metal. Night freezing glass. But waking,” said this car, “that’s the worst goddamn part of all.”

Maybe I lost control. Maybe I did it on purpose. Truth is, I’m not really sure myself. One second we were on the road. The next? Careening down the sidewalk as joggers and dog-walkers dived away, looking more angry I’d say than fearful.

“Do not despise nor abhor the affliction of the afflicted,” the car was saying like in prayer to some demonic, subcompact god. As for me–well, I pictured a fiery wreck, twisted metal, an impact strong enough to separate the car from itself and put an end to its misery. I had my own miseries, too. Wondered if an end might be achieved in this regard as well.

By now my hands had released the steering wheel. The car rolled over a bush, flattened a kiddie pool, slammed into the side of a garage at which point motion ceased except for that which caused my head to smack the horn.

When I came to there in the driveway was a tow truck, in the road an ambulance and police cruiser. There on the porch was the owner of the garage and the home to which it was connected, gesturing theatrically at a trio of officers.

I kinda unfolded myself from around the steering wheel then and opened the door, staggering out onto the lawn.

The car I should say was not doing well. Like it was still running, sure, but had this black exhaust sputtering from its tailpipe. Like this dark fluid was oozing out from somewhere into the ground.

“It‘ll probably cost more to fix than what you paid for it,” the tow truck driver was saying, appearing beside me. “My advice? Just junk it.”

“Junk it,” I told him almost like I’d come up with the idea myself. Vision blurring, I signed his forms and staggered further away. No one seemed to notice and for this I was thankful. I couldn’t afford an ambulance ride and besides which I was in the mood for a walk. I was in the mood I suppose for a little contemplation: I wasn’t any good at the marriage thing. I wasn’t that great of a father really, either. Wasn’t even a decent car owner. In fact, my driving skills were very much in question.

As I left the car behind, I could hear its clicking laugh. This, too, no one noticed and it occurred to me–not for the first time–that maybe this car was communicating at a frequency to which only I was attuned.

As I left the car behind, I could hear its clicking laugh. This, too, no one noticed and it occurred to me–not for the first time–that maybe this car was communicating at a frequency to which only I was attuned.

“Axels to axels,” it was saying. “Rust to rust.”

_______________